Quote of the Week

"The theologians have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it."

"The theologians have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it."Philip Berryman

Labels: liberation theology

"The theologians have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it." -- Philip Berryman

"The theologians have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it."

"The theologians have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it."Labels: liberation theology

"I am so tempted to give up on a Christianity where preachers from their pulpits preach a personal piety that ignores public responsibility. Like Muslim apologists who keep reminding us that true Islam does not condone terrorist acts, I am placed in the position of having to argue that true Christianity does not condone torture."

"I am so tempted to give up on a Christianity where preachers from their pulpits preach a personal piety that ignores public responsibility. Like Muslim apologists who keep reminding us that true Islam does not condone terrorist acts, I am placed in the position of having to argue that true Christianity does not condone torture."Labels: ethics, liberation theology, peacemaking, quotes, recommended reading

Today marks the 20th anniversary (September 11, 1988) of the destruction of St. Jean Bosco Church in the slums of Port-au-Prince. While Father Jean-Bertrand Aristide was giving mass, armed thugs working for the Henri Namphy regime entered the church and, in a siege that lasted several hours, massacred over twenty parishioners and injured many, many more before setting fire to the church. While Aristide managed to escape with his life, the incident eventually led to his expulsion from the Salesian order on December 15, 1988. Aristide, a liberation theologian and Roman Catholic priest, led the popular movement that led to the downfall of the Duvalier regime on February 7, 1986. Twenty years (and two not-so successful Aristide presidencies) later, Haiti continues to be mired in poverty and violence.

Today marks the 20th anniversary (September 11, 1988) of the destruction of St. Jean Bosco Church in the slums of Port-au-Prince. While Father Jean-Bertrand Aristide was giving mass, armed thugs working for the Henri Namphy regime entered the church and, in a siege that lasted several hours, massacred over twenty parishioners and injured many, many more before setting fire to the church. While Aristide managed to escape with his life, the incident eventually led to his expulsion from the Salesian order on December 15, 1988. Aristide, a liberation theologian and Roman Catholic priest, led the popular movement that led to the downfall of the Duvalier regime on February 7, 1986. Twenty years (and two not-so successful Aristide presidencies) later, Haiti continues to be mired in poverty and violence.Labels: church history, Haiti, Human Rights, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, liberation theology

"When we read the Book of Acts, all too often we misinterpret the book's central thesis. Most of us have been taught that Acts is the story about how the church converted the world to Jesus Christ. In reality, the book of Acts is the story as to how the church constantly had to be converted in order to make the message of Jesus Christ relevant to a hurting and spiritually hungry world."

"When we read the Book of Acts, all too often we misinterpret the book's central thesis. Most of us have been taught that Acts is the story about how the church converted the world to Jesus Christ. In reality, the book of Acts is the story as to how the church constantly had to be converted in order to make the message of Jesus Christ relevant to a hurting and spiritually hungry world."Labels: Acts, evangelism, hermeneutics, liberation theology, quotes, recommended reading

"Why is it that a book that for its first readers was a word of comfort causes terror in us? Could it be that our place in the world and in society is very different from the position of those early Christians? Those churches in Asia looked upon the cataclysms announced in Revelation as a metaphor for their final vindication. It is difficult for us today to see things in the same light. Could it be that we have such an investment in the present order that we do not want it to pass away? Could it be that our perspective comes closer to that of 'the kings of the earth and the magnates and the generals and the rich and the powerful'? If we really saw and experienced the wickedness of the present order and were among the many who suffer as a consequence of that order would we not see its end with the same joy with which the first readers of Revelation were invited to see it?" (Italics mine)

"Why is it that a book that for its first readers was a word of comfort causes terror in us? Could it be that our place in the world and in society is very different from the position of those early Christians? Those churches in Asia looked upon the cataclysms announced in Revelation as a metaphor for their final vindication. It is difficult for us today to see things in the same light. Could it be that we have such an investment in the present order that we do not want it to pass away? Could it be that our perspective comes closer to that of 'the kings of the earth and the magnates and the generals and the rich and the powerful'? If we really saw and experienced the wickedness of the present order and were among the many who suffer as a consequence of that order would we not see its end with the same joy with which the first readers of Revelation were invited to see it?" (Italics mine)Labels: hermeneutics, liberation theology, quotes, Revelation

"When people live under oppressive structures, they turn to the Bible for the strength to survive another day, not to figure out how long a day lasted in Genesis 1. The Bible is not read with the intellectual curiosity of solving cosmic mysteries; rather, most people on the margins look to the text to find guidance in dealing with daily life, a life usually marked by struggles and hardships. Debates over the scientific validity of the Scriptures become a luxurious privilege for those who do not endure oppressive and discriminating structures."

"When people live under oppressive structures, they turn to the Bible for the strength to survive another day, not to figure out how long a day lasted in Genesis 1. The Bible is not read with the intellectual curiosity of solving cosmic mysteries; rather, most people on the margins look to the text to find guidance in dealing with daily life, a life usually marked by struggles and hardships. Debates over the scientific validity of the Scriptures become a luxurious privilege for those who do not endure oppressive and discriminating structures."Labels: creation, evolution, hermeneutics, liberation theology, quotes

. . . and, in this instance, the Son of God as well.

Labels: Christology, liberation theology, recommended reading

Tony Campolo offers a helpful answer to that question here:

Tony CampoloRead the rest of the article here.

What is Liberation Theology?

With all the upset over Jeremiah Wright and his so-called Liberation Theology, many have been asking what Liberation Theology is all about. Well, it is not very complicated! It is the simple belief that in the struggles of poor and oppressed people against their powerful and rich oppressors, God sides with the oppressed against the oppressors.

Those who adhere to Liberation Theology point out that all through the Bible we find that God always champions the cause of those who are poor and beaten down as they struggle for dignity, freedom and economic justice. When the children of Israel cry out for help as they suffer the agonies of their enslavement under Pharaoh, God hears their cry and joins them in their fight for freedom. God sides with the Jews as they seek deliverance from Egyptian domination.

Labels: black theology, liberation theology, Tony Campolo

"The saddest part of this situation is that such cheap theology turns out to be very expensive. The price we pay for such theology is that we do not dare speak of our sufferings and anxieties, for they are our fault and an indication of our own corruption and lack of faith. The price for such theology is that the poor must internalize their oppression, for they are told that if they are poor it is because of their sin. The price for such theology is a church in which, in contradiction to what is taught in Scripture, the poor, the orphan, and the suffering are shunned, and the rich, the powerful, and the healthy are praised. In short, the price of such theology is abandoning the cross of Christ and its meaning."

"The saddest part of this situation is that such cheap theology turns out to be very expensive. The price we pay for such theology is that we do not dare speak of our sufferings and anxieties, for they are our fault and an indication of our own corruption and lack of faith. The price for such theology is that the poor must internalize their oppression, for they are told that if they are poor it is because of their sin. The price for such theology is a church in which, in contradiction to what is taught in Scripture, the poor, the orphan, and the suffering are shunned, and the rich, the powerful, and the healthy are praised. In short, the price of such theology is abandoning the cross of Christ and its meaning."Labels: Hispanics, liberation theology, prosperity theology, quotes

Tracy Kidder, Mountains Beyond Mountains. New York: Random House, 2004.

Mountains Beyond Mountains tells the story of Dr. Paul Farmer, a medical anthropologist and practicing physician whose work in Haiti has made significant inroads in treating tuberculosis and AIDS patients. For those who are interested in learning about the day-to-day realities of healthcare faced by Haitians and others living in underdeveloped countries, this book is an excellent introduction to the issues at hand. While Farmer is not a missionary, his work has been significantly shaped by the best of liberation theology and international development theory. To understand Farmer’s work is to gain insight into many of the issues that missionaries must struggle with as they seek to minister effectively in cross-cultural and poverty-stricken contexts. I highly recommend this book. But beware! Once you pick it up, you won’t be able to put it back down until you’ve finished it.

Mountains Beyond Mountains tells the story of Dr. Paul Farmer, a medical anthropologist and practicing physician whose work in Haiti has made significant inroads in treating tuberculosis and AIDS patients. For those who are interested in learning about the day-to-day realities of healthcare faced by Haitians and others living in underdeveloped countries, this book is an excellent introduction to the issues at hand. While Farmer is not a missionary, his work has been significantly shaped by the best of liberation theology and international development theory. To understand Farmer’s work is to gain insight into many of the issues that missionaries must struggle with as they seek to minister effectively in cross-cultural and poverty-stricken contexts. I highly recommend this book. But beware! Once you pick it up, you won’t be able to put it back down until you’ve finished it.Labels: Anthropology, book reviews, Haiti, liberation theology, Medicine, Paul Farmer, recommended reading

Ethics Daily has just run an article on Miguel De La Torre's latest book Liberating Jonah: Forming an Ethic of Reconciliation.

New Book Examines Jonah Story from the Underside of OppressionClick here for the rest of this article.

Bob Allen

11-01-07

The Old Testament story of Jonah is more than a fairy tale about a man being swallowed by a whale, and even more than an evangelical call to preach the gospel to those in foreign lands, but instead a model for reconciliation between the haves and the have-nots, says a new book.In Liberating Jonah: Forming an Ethic of Reconciliation, EthicsDaily.com columnist Miguel De La Torre suggests that the reading of Jonah he learned in Sunday school--that God is calling America, as the most powerful nation in the world, to carry the light to those in darkness--is upside down.

The power in the Book of Jonah is the Assyrian Empire, brutal conquerors of the Israelites whom Jonah and his contemporaries likely viewed with hatred and scorn. Reading the text from the perspective of the disenfranchised, De La Torre says the United States is not the hero but the villain.

Labels: liberation theology, recommended reading

Miguel A. De La Torre, Doing Christian Ethics from the Margins. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2004. xvi + 280 pp. Paperback, $20.00. ISBN 1-57075-551-5.

Labels: book reviews, ethics, liberation theology, recommended reading

The feminist theologian Rosemary Radford Ruether attempts to answer precisely this question in an article that she wrote two years ago for the National Catholic Reporter.

Five years ago I offered a course in Latin American liberation theology at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, Calif. We studied this theology in the context of the history of church and society in Latin America from the time of the Spanish conquest, focusing on the developments of the 1960s and new stages of Latin American liberation theology in the 1990s to 2000. I was astonished to be told by several students that Latin American liberation theology had been declared to be "dead" or "over with" by some professors at the school. Since that time I have heard several such announcements of the death of liberation theology from students and faculty. It is also evident that few North American theological seminaries are offering courses on Latin American liberation theology today. What is going on?Contrary to the prevailing opinion amongst many American theologians, Ruether explains that the situation on the ground in Latin America and the Caribbean is actually much different, noting that liberation theology has been most recently characterized by diversification rather than decline.

What has happened to Latin American liberation theology in the last 15 years is not that it has dried up, but rather that it has greatly diversified. It was rightly criticized for being too narrowly focused on class and economic hierarchies and neglecting other dimensions of social relations, such as race, ethnicity and gender. In the last two decades this has been rectified by a great flowering of Latin American feminist theology, all of which sees itself as rooted in liberation theology but expanding through the new recognition of gender hierarchies. Likewise there has been since 1992 a flowering of indigenous theologies, or teologia india, with many encuentros (meetings) across Latin America, especially in the Andean region.That being said, Ruether goes on to suggest that proclamations that liberation theology is "dead" are premature and reflect the increasing insularity of American culture and academics.

African Caribbean and African Brazilian people are also developing distinct articulations of liberation and feminist theologies in these cultural contexts. There is a burgeoning interest in dialogue between Christianity and indigenous and African-Latino religions: Clara Luz Ajo in Cuba is among those pursuing this kind of reflection in relation to Africa Cuban religions, such as Santeria. Issues of ecology have also attracted theological interest both from theologians such as Leonardo Boff and those who take ecofeminism as their method of theological reflection such as Ivone Gebara in Brazil and the Conspirando network in Chile.

Far from being over with, liberation theology lives in the faith of that sector of Latin American ecumenical Christianity, in Catholics and Protestants who work together both in seminaries and at the grass roots from the perspective of hope for greater justice. The pronouncements that Latin American liberation theology is dead are not only premature, but I think are another indication of the growing parochialism and insularity of the U.S. North American consciousness in the face of a world that is increasingly critical of our way of life.Ruether's assessment of the state of liberation theology probably comes as no surprise to many of us residing in the Caribbean and Latin America. More importantly, it serves as a reminder to persevere in the task of creatively articulating a theology that is both faithful to scripture as well as the sociocultural context within which we live, worship, and seek to minister.

Labels: liberation theology

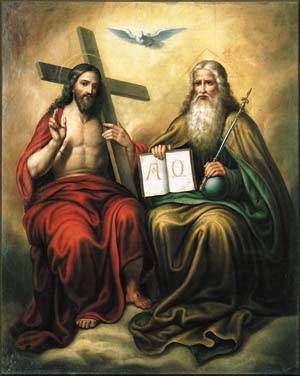

Yesterday, I posted a quote by the African American theologian James Evans that challenges us to recognize how the very nature and character of God is often misrepresented theologically in order to justify racism, classism, sexism, neo-colonialism and many of the other –isms that plague our fallen world. With this in mind, it should be no surprise that theologians representing a variety of historically oppressed groups have attempted to construct theological alternatives to the prevailing racist, classist, sexist, and neo-colonialist images of God that have been propagated by the dominant culture.

Yesterday, I posted a quote by the African American theologian James Evans that challenges us to recognize how the very nature and character of God is often misrepresented theologically in order to justify racism, classism, sexism, neo-colonialism and many of the other –isms that plague our fallen world. With this in mind, it should be no surprise that theologians representing a variety of historically oppressed groups have attempted to construct theological alternatives to the prevailing racist, classist, sexist, and neo-colonialist images of God that have been propagated by the dominant culture.Holy, Holy, Holy! Lord God Almighty!

God in Three Persons, blessed Trinity!

Labels: doctrine of God, liberation theology, reconciliation, Trinity

"Militarism, a debased view of human sexuality, blind consumerism, ideas of racial supremacy, and xenophobia disguised as patriotism are among the contemporary idols that have asserted an indisputable divine mandate."

"Militarism, a debased view of human sexuality, blind consumerism, ideas of racial supremacy, and xenophobia disguised as patriotism are among the contemporary idols that have asserted an indisputable divine mandate."Labels: black theology, doctrine of God, liberation theology, quotes

"Actions speak louder than words, and prophetic actions speak louder than prophetic words."

"Actions speak louder than words, and prophetic actions speak louder than prophetic words."Labels: liberation theology, quotes

Justo L. González, Three Months with Revelation. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2004. 184 pp. Paperback, $11.00. ISBN 0-687-08868-2

Unlike many of the current popular writings on Revelation, this new devotional guide is not just another outline of end-times events. Instead, Justo González--a Cuban American theologian--approaches Revelation in light of the oppressive context of the Roman Empire in which it was written, arguing that it sought to comfort and bring hope to persecuted churches in Asia Minor. Consequently, its primary significance for today is that it serves as a call to obedience amidst hardship and persecution. Though, it is often misread as a message of terror by those who enjoy economic privilege while living in spiritual complacency.

Unlike many of the current popular writings on Revelation, this new devotional guide is not just another outline of end-times events. Instead, Justo González--a Cuban American theologian--approaches Revelation in light of the oppressive context of the Roman Empire in which it was written, arguing that it sought to comfort and bring hope to persecuted churches in Asia Minor. Consequently, its primary significance for today is that it serves as a call to obedience amidst hardship and persecution. Though, it is often misread as a message of terror by those who enjoy economic privilege while living in spiritual complacency.Labels: book reviews, liberation theology, recommended reading

Bob Corbett has recently written a very lengthy and detailed review of Alex Dupuy's new book on Jean-Bertrand Aristide, titled The Prophet and Power (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006).

Bob Corbett has recently written a very lengthy and detailed review of Alex Dupuy's new book on Jean-Bertrand Aristide, titled The Prophet and Power (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006).During Aristide's tenure as a parish priest, Corbett explains:Alex Dupuy’s over-arching thesis is quite different. He makes a strong case that this story lacks any blameless good folks. Whether it is Aristide’s person and personality, the activities of his party and supporters, or any one or group of his Haitian opposition or the U.S.-led international community, each and everyone comes in for severe and intelligent criticism. There just isn’t, on Dupuy’s account, a “right” or “good” side in this story for the country of Haiti. It is a terrible tragedy of the repeated history of the fall of one failed state, being replaced by an equally failed state.

The first Aristide is, on Dupuy’s account, an appealing figure, but with a radical contradiction in his person and views. I am impressed and persuaded by Dupuy’s analysis that THIS early Aristide is best understood as a man of contradictory tendencies (italics mine): a reformer with a true passion to bring about reforms consistent with the liberation theology concept of “the preferential option of the poor,” yet as a personal revolutionary and one who sees himself as not only a prophet, but as a leader not responsible to others.Later upon being elected to the presidency of Haiti, these contradictions in Aristide's personality coupled with Haiti's volatile internal situation proved to be his undoing:

I have long argued that Aristide had a brilliant career as a liberation theology priest who helped to bring about the demise of Haiti's corrupt Duvalier regime, but that he failed dismally as Haiti's first freely elected president. Dupuy's book helps us to understand why. Clearly, The Prophet and Power is a must-read book for anyone interested in understanding the legacy of Jean-Bertrand Aristide as well as the broader issues of why Haiti remains stubbornly ungovernable.He preached democracy and revved up a great deal of support for this notion, yet he had an almost impossible time acting democratically within Lavalas or as president. He seemed deeply committed to his own vision and one was either with him or against him. The clash was devastating.

More importantly, he preached democracy, seems to have wanted a rule by law, but faced enormous forces against him, many of which were using physical force. Thus the more revolutionary, prophetic Aristide turned to the non-democratic “power of the people” to protect him.

Perhaps what got Aristide in the greatest mess was his advocacy of and refusal to deny the use of Pere Lebrun (fiery necklacing of people with tires). Not only was this a terrifying threat to government officials and opposition people in the bourgeoisie. It was a frightening inconsistency – at times Aristide seemed to be agreeable to working with the opposition and compromising here and there, and at other times he would be talking of how wonderful this tool was. It created strong doubt in the minds of many of the reliability of any alliance with Aristide.

Labels: book reviews, Haiti, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, liberation theology, recommended reading